This article is part of a series in partnership with The Signal. Sidik will be a speaker at the 2023 Oslo Freedom Forum in New York this month.

As the United Nations General Assembly convened its annual meeting in New York City this week, a small event on the sidelines provoked anger from China’s UN mission. The event, held on September 19, was a forum to detail human-rights abuses in the Uyghur-majority region of northwestern China—Xinjiang Province, as Beijing calls it—and urge world leaders to pressure the People’s Republic to end them. China’s UN delegation warned global diplomats not to attend, saying the event would spread lies and “disrupt China’s peaceful development.”

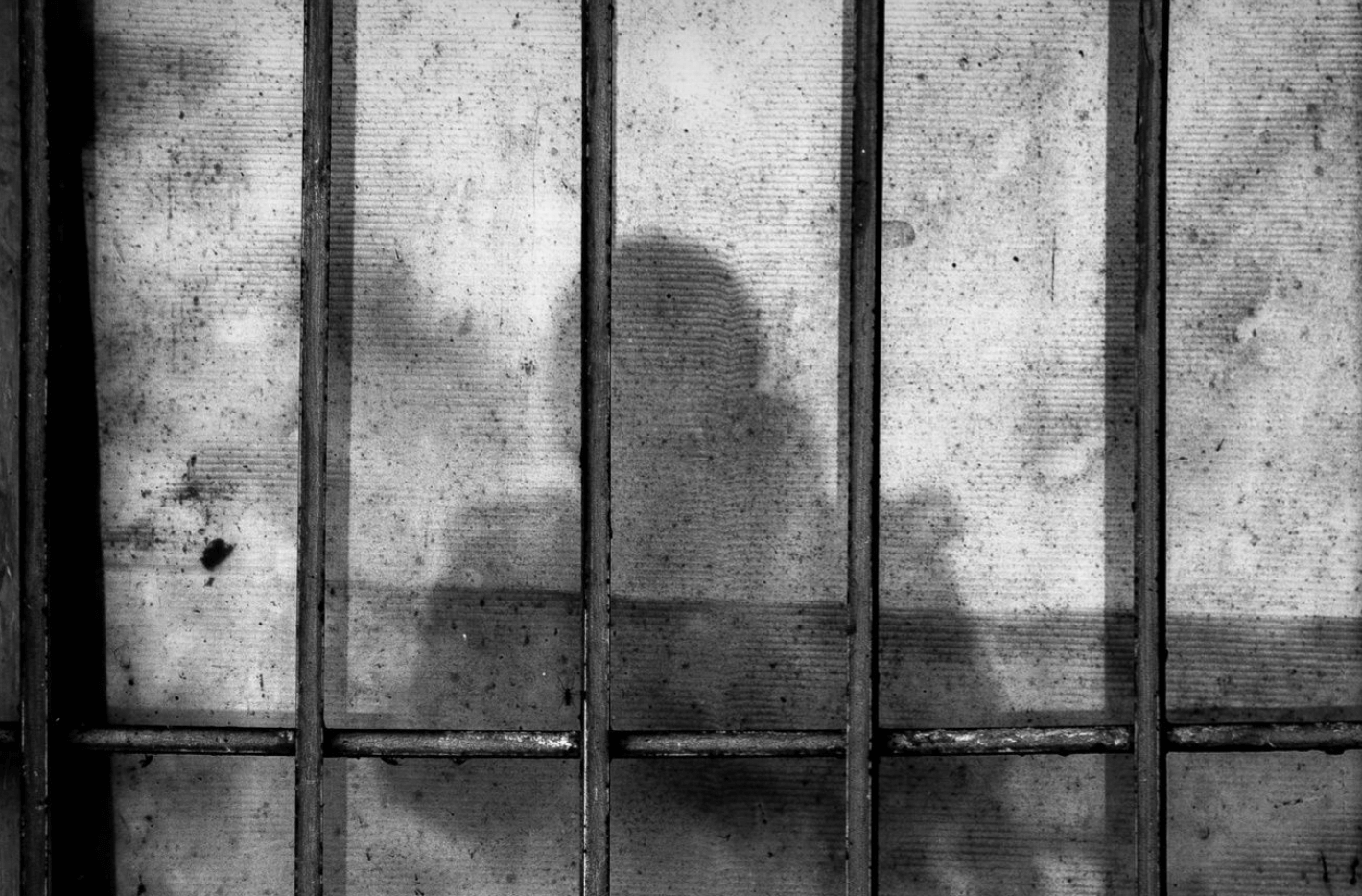

Meanwhile, more than 1 million people in the Uyghur region have been incarcerated since Beijing’s crackdown against Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other Muslims in the region started seven years ago. The Chinese Communist Party has constructed a network of prisons, internment camps, and forced-labor camps, subjecting these minorities to forced birth control, abortions, and sterilization—along with a campaign to “reeducate” them away from Islam and their ethnic traditions and identities. What exactly has the Party been doing there?

Kalbinur Sidik was a schoolteacher for 28 years in Ürümqi, the largest city in the Uyghur region. She was imprisoned in early 2017 and forced to teach the Chinese language in two internment camps, where she was forcibly sterilized in 2019. She left China in late 2019, after her daughter, who lives in the Netherlands, campaigned for her release. As Sidik explains, the Chinese government has built an elaborate surveillance regime to track people in the region—in their homes and throughout their communities. Many who’ve had any contact with the outside world, or who’ve outwardly displayed their Muslim faith, end up in internment camps, where they’re shackled, unable to clean themselves, poorly fed, and tortured. Those detained between the ages of 18 and 40 are sent on to forced-labor camps.

Michael Bluhm: What’s day-to-day life like in the Uyghur region?

Kalbinur Sidik: I was a teacher. Today, students and teachers still go to school, but Uyghur teachers don’t teach anymore. They’re not in the classrooms; they do maintenance.

Uyghur students are always subjected to change: Their teachers and textbooks change all the time. Even their classmates have changed. Some schools had only Uyghur students before 2017 but now have more and more Han Chinese students. The government has also implemented a boarding policy, meaning parents can’t see their children as much as they could before 2017.

When you go in or out of a school in the Uyghur region, you have to scan your face. At indoor shopping malls and even outdoor shopping strips, there are facial scanners about every 15 meters. At government buildings, you have to do facial and iris scans.

In Ürümqi, there is a police checkpoint every 500 meters and a larger police station every kilometer or two. People usually don’t want to go out when they don’t have to work, because they get stopped by the police all the time. They can barely put their ID cards back in their pockets.

But if you don’t go out, then the security services see that your ID card hasn’t been scanned recently, so they come to your home and ask, Why aren’t you going out?

Life goes on, but it’s a different life. You’re being pushed to go out, and you’re being pushed not to go out. People throughout the region live in intimidation and fear. Every day, they feel as if they’re just waiting for their turn to be detained.

Bluhm: How far does the control of people’s day-to-day life in the region go?

Sidik: What happened to me in September 2016 is typical. Everyone in the city was asked to submit to a full medical exam, where we had to give a blood sample, have iris scans and facial scans, give a voice sample, and have images of our faces taken from various angles. That year, the government started collecting this information from all Uyghurs.

Before then, there was no gate at the apartment building where I lived with my family. People could come and go freely. But now, we all had to scan our faces and eyes before being allowed to enter the building.

After the scans, only one person is supposed to go through the gate. One time, another person came in through the gate behind me without doing the scans, so the police came to my home and asked me who that person was, why she was in the building, and so on.

On top of our building, there is a huge machine for recording audio. It recognizes the voice samples of everyone who lives in the building. For example, a teenager from the building was in the inner courtyard one day, asking why Uyghurs couldn’t wear their traditional hats anymore. He was just hanging out with some other young people from the building, with no adults or police officers around. The next day, he was taken into the police station. The machine on the roof had heard and recorded him.

Each home also has a QR code mounted inside. Every time the security service comes in, they scan the code. I asked them what the code was, and they said it had all the information about the household: Who lives there, what we watch on TV, what we talk about, who visits us, and so on. It was all in the QR code.

Bluhm: Who ends up in the internment camps, and why?

Sidik: Most of the people detained there are Uyghurs, other Muslims, or Kazakhs. In Ürümqi, there are not a lot of Kazakhs; Kazakhs are mostly detained in the northern part of the region. In the two detention camps where I worked, there were only Uyghurs.

People are interned for three main reasons. One group is people with connections outside China—anyone who has traveled abroad, has relatives abroad, makes calls abroad, or sends money out of the country. Another group is Muslims: any Muslim women who wear, or even once wore, the hijab—or anyone with a Quran or religious items in their homes, or even religious apps on their phone. The last group is people who have apps such as Facebook, Instagram, or WhatsApp on their phones, because they could be in touch with people outside China.

Anyone who speaks out against the government is immediately sentenced to prison—they don’t even go through the detention camps. People who simply talk about protests—even if just at home—are also sentenced directly to prison.

Bluhm: What happens to people in these camps?

Sidik: Those detained are usually kept in handcuffs and with chains on their legs. The cells have only children’s chairs. There’s not enough food. There are no beds. They’re not allowed to shower. There is no light in the building, so everyone looks pale, weak, and sick.

Everyone has a number sewn into their uniform, and they are called by their numbers—never by their name.

They are interrogated very frequently, in special basement rooms equipped for torture. There are a few main torture techniques regularly used in these interrogations.

People are only released if they are in very bad condition, mentally or physically. I’ve heard of many people who died on their way to the hospital.

Bluhm: What about the forced-labor camps—what goes on there?

Sidik: I worked in two internment camps, and I was inside two forced-labor camps.

Anyone between 18 and 40 years old in a concentration camp is usually transferred to a forced-labor camp. In the forced-labor camps, the prisoners work about 18 hours a day. Sometimes they get a small salary, but it is usually late or never paid at all. They do not have any contact with their families when they are in the camps. Forced laborers in Ürümqi work six days a week. They are allowed to go home on Sundays, but they have to return to the camps on Sunday night.

The company where my husband works was turned into a forced-labor facility around 2018. All the people there doing forced labor were younger than 30. The company mainly makes industrial products. Its headquarters are in Beijing, and all its products are exported to neighboring countries.

Bluhm: In 2021, the U.S. Congress passed the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which requires any company importing goods produced in the region into America to certify that they weren’t made by forced labor. We know a lot of clothing and textiles are made by forced labor in the Uyghur region. What other products are?

Sidik: I went to two forced labor camps. One was my husband’s company. The other mainly produces foods, especially traditional Uyghur specialties, like our style of bread. The government then exports these as “cultural products.”

In the women’s concentration camp where I worked, all the women’s hair was cut short. Then the hair was sent to forced-labor camps, where beauty products were made for export, such as hair extensions.

Bluhm: Do people in the forced-labor camps know anything about where the products they make wind up?

Sidik: They don’t know anything. Most people in the forced-labor camps don’t even know that what they’re doing is considered forced labor. It’s an order from the state. If the state sends you somewhere to work, you have to go. You don’t have any choice. It’s just what the government tells you to do.

Depending on where you are coming from, you might not perceive the conditions as others would. For those coming from a concentration camp, a transfer to a forced-labor camp is an improvement.