Introduction:

In early January, tens of thousands of people across Kazakhstan protested after a sharp rise in the price of gas. Although most of the protests were peaceful, in several cities, rioters attacked government buildings in what looked like a power struggle within Kazakhstan’s elite. The government of Kazakhstan brutally cracked down on both the peaceful protests and the riots. Details of the crackdown are still difficult to verify because the government shut off internet access, and few independent journalists are allowed to operate in the country. Official sources suggest that at least 225 people died, and over 10,000 have been imprisoned.

The protests may have been sparked by price spikes, but protesters were expressing their anger over deeper issues with Kazakhstan’s authoritarian regime, including an economy based on corruption and rampant human rights violations. This blog series puts the protests in Kazakhstan into context, by examining the history and root causes of the dissatisfaction in the country, including the cult of personality and corruption at the foundation of its regime.

By Kenza Bouanane

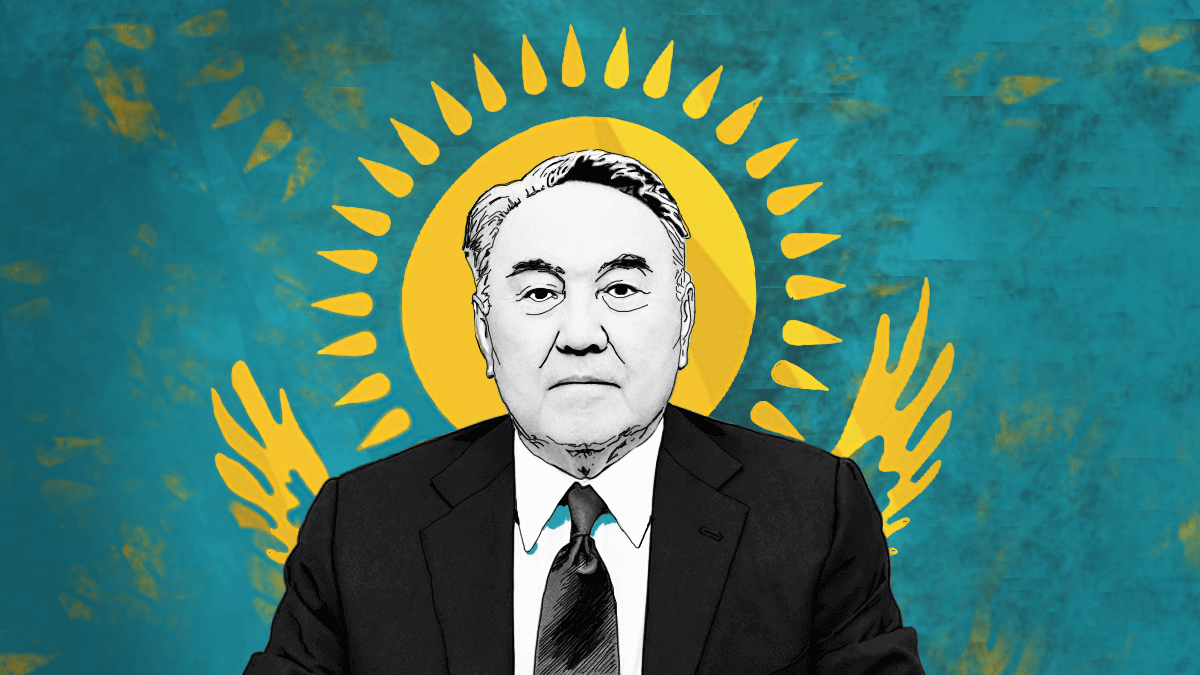

For most of its independent history, Kazakhstan has been ruled by one man: Nursultan Nazarbayev. In 1989, Nazarbayev took over the post of First Secretary of the Communist Party in Kazakhstan when his predecessor was recalled back to Moscow after a series of deadly riots. As a lifelong and ambitious member of the Communist Party, Nazarbayev managed to hold onto power as the first president of an independent Kazakhstan, while also maintaining a close relationship with Moscow after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Over the course of the following three decades, he maintained much of the repressive nature of the Communist rule in his country, and slowly transformed the former Soviet state into a kleptocratic regime that answered only to himself and his family, taking control of major state-owned companies and making it impossible for the political opposition to mount a meaningful independent challenge to his rule. He sold an image of modernity and prosperity to the outside world, but his legacy is one of repression, corruption, and authoritarianism.

Following the playbook of so many other autocrats in the region and beyond — including Emomali Rahmon in Tajikistan and Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov in Turkmenistan — Nazarbayev spent significant state resources during his rule to build a cult of personality around himself. Nazarbayev bestowed upon himself the title of “Father of the Nation,” put his portrait on banknotes, and constructed extravagant monuments and skyscrapers bearing his name. All of these gestures sought to immortalize the image of the dictator into everyday life, even after his rule ended. It is the reflection of a one-man rule political system where no dissent is allowed, given that anything that can be construed as an insult to the nation’s “father” is punished by law.

In 2019, an octogenarian Nazarbayev, looking to avoid the fate of Uzbekistan’s dictator Islam Karimov and die in office, finally handed over the presidency to Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, the then-Chairman of the Senate and a close political ally, but he continued to exert tremendous influence over the government. He may no longer hold the title of president, but the cult of personality that he established reminds everyone in the country not just of where power really lies, but also tells the fictionalized story of an all-powerful man who is single-handedly responsible for the very existence of modern Kazakhstan and its alleged successes, from forging alliances abroad to overseeing decades of “stability.” Tokayev even renamed the capital Astana to Nursultan in his honor upon his resignation.

The myths surrounding former dictators are often also used by their successors to bolster their credibility and ensure their autocratic rule remains unchallenged — even after they are gone for good. It is no surprise, for example, that Cuban dictator Diaz-Canel has ramped up the Communist Party’s devotion to the late dictator Fidel Castro as the regime continues its massive crackdown on civil society, or that Karimov’s cult of personality grew after his death, while his successor attempted to make merely cosmetic changes to the autocratic regime Karimov left behind.

However, unlike the Castros or Karimov, Nazarbayev and his family continue to hold public office and political power, as well as an immense amount of wealth which they plundered from the country. When Tokayev took over the presidency, the former dictator remained a member of the Security and Constitutional Councils, had the final word on cabinet assignments, and even continued to represent the country in international settings. Although Tokayev had hailed himself as a reformer, nothing truly changed — including the veneration of the former dictator. Several of his family members also hold leadership roles in energy and utility companies, and his daughter, Dariga Nazarbayeva, believed by many to be Nazarbayev’s preferred pick for a long-term true successor to the presidency, continued to hold the position of Chairman of the Senate, one of the most powerful offices in the country, upon his resignation.

Over the past two years, however, signs of disagreements and power struggles between Tokayev and the Nazarbayev family have started to emerge, despite the regime’s best efforts to show unity. This became evident when, in 2020, Dariga Nazarbayeva was demoted from her position as Senate leader. Furthermore, the recent protests revealed how strained the relationship between Tokayev and Nazarbayev is. Protesters tore down statues of Nazarbayev, Tokayev took over the leadership of the country’s ruling party, government officials stopped using the name Nursultan to refer to the capital, and Nazarbayev stepped down from his leadership position on the Security Council, a powerful body created by Nazarbayev himself in the 1990s that was tasked with ensuring the supremacy of the presidency over security matters. Nevertheless, Nazarbayev has already come out to deny there is any conflict within his party or the government of Kazakhstan, and Tokayev has even hinted that his role at the helm of ruling the Nur Otan Party might be temporary.

Following the January 2022 protests, which were partly motivated by a rejection of Nazarbayev’s legacy, we may see Kazakhstan begin to shake off its influence. However, it is clear that Nazarbayev’s toxic influence over Kazakhstan will not disappear anytime soon. The cult of personality he built over the years bolstered his grip on power well beyond his resignation and overloaded the public sphere with his image, equating the very spirit of the nation with his figure, making any challenge to his power difficult.

Tokayev may want to curb Nazarbayev’s influence, but not because he is a democratically-minded reformer. He is part of the repressive, kleptocratic machinery that festered in Kazakhstan for decades, and he is likely to use the former dictator’s image to gain support from those still loyal to Nazarbayev, as many other strongmen before him have done. The future of democracy in Kazakhstan will undoubtedly hinge on the dismantling of the myth of Nazarbayev as a benevolent leader and challenging all those who profited from his rule, including Tokayev.

Conclusion:

The Kazakhstani regime eventually promised to present a package of reforms later this year to mitigate some of the rage expressed by protesters, but it is unlikely to change the nature of a regime that has thrived on corruption, repression, and a cult of personality for over three decades. Though the government crushed these most recent protests, resentment in Kazakhstan continues to simmer. Only democratization, aided by a concerted effort by Western democracies to stamp out corruption, can prevent further turmoil.

Graphics by Mariana Bernardez

Read the complete “Kazakhstan in Context: Corruption, Repression, and Cult of Personality” blogs series below: