From September to November of 2020, Armenia and Azerbaijan fought a bloody war over the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh and its surroundings. After 44 days of combat, a Russian-negotiated ceasefire came into force, ending hostilities with Azerbaijan as the victor.

Now that Azerbaijan has won, it is the responsibility of the Azerbaijani government to maintain peace and protect the people it governs. Unfortunately, though violence has abated, Azerbaijan’s authoritarian regime has not taken appropriate steps to cool ethnic tensions. Part of the problem is authoritarianism itself. Long-term peace cannot happen without democratic reform in Azerbaijan.

Nagorno-Karabakh is an ethnically Armenian enclave that is internationally recognized as a part of Azerbaijan. Since 1994, the territory as well as seven historically Azerbaijani provinces have been governed by the Republic of Artsakh, an Armenian-backed breakaway state. This was the result of the first Nagorno-Karabakh War of 1988-1994 which was decisively won by Armenia, and resulted in over a million refugees, tens of thousands of casualties on both sides, and an uneasy peace amid latent ethnic hatred.

Credit: bbc.co.uk

This second Nagorno-Karabakh War is practically a reversal of the first. This time, with strong Turkish support, Azerbaijan has succeeded in reclaiming all seven historically Azerbaijani provinces as well as parts of Nagorno-Karabakh. The Republic of Artsakh is greatly diminished, and connected to Armenia by a single road monitored by Russian peacekeeping forces. An estimated 90,000 Armenians have been left displaced by the war.

A steady stream of photos and videos have poured out of the area documenting human rights abuses committed by soldiers. In two of some of the most gruesome videos, Azerbaijani soldiers can be seen beheading Armenian captives, and another one shows Armenian soldiers cutting the throat of an Azerbaijani border guard. Though both governments have promised to identify and bring the perpetrators to justice, Azerbaijan has already dismissed many accusations as fake, and unlike Armenia, Azerbaijan did not allow independent journalists access to sensitive areas, making it difficult to verify claims and document evidence. Both sides have accused each other of committing human rights violations, but it is now Azerbaijan’s responsibility as the victors to bring peace.

Unfortunately, the ethnic Armenians who now find themselves governed by Azerbaijan are right to be skeptical that they will be treated humanely. The sheer number of Azerbaijani soldiers that appear comfortable filming atrocities, as well as the widespread denial of these atrocities in Azerbaijan, are only recent developments in Azerbaijan’s history of ignoring or welcoming abuses against Armenians. In 2012, for example, an Azerbaijani officer who murdered an Armenian with an axe in Budapest was extradited back home, and promptly given a hero’s welcome, including a pardon and a promotion.

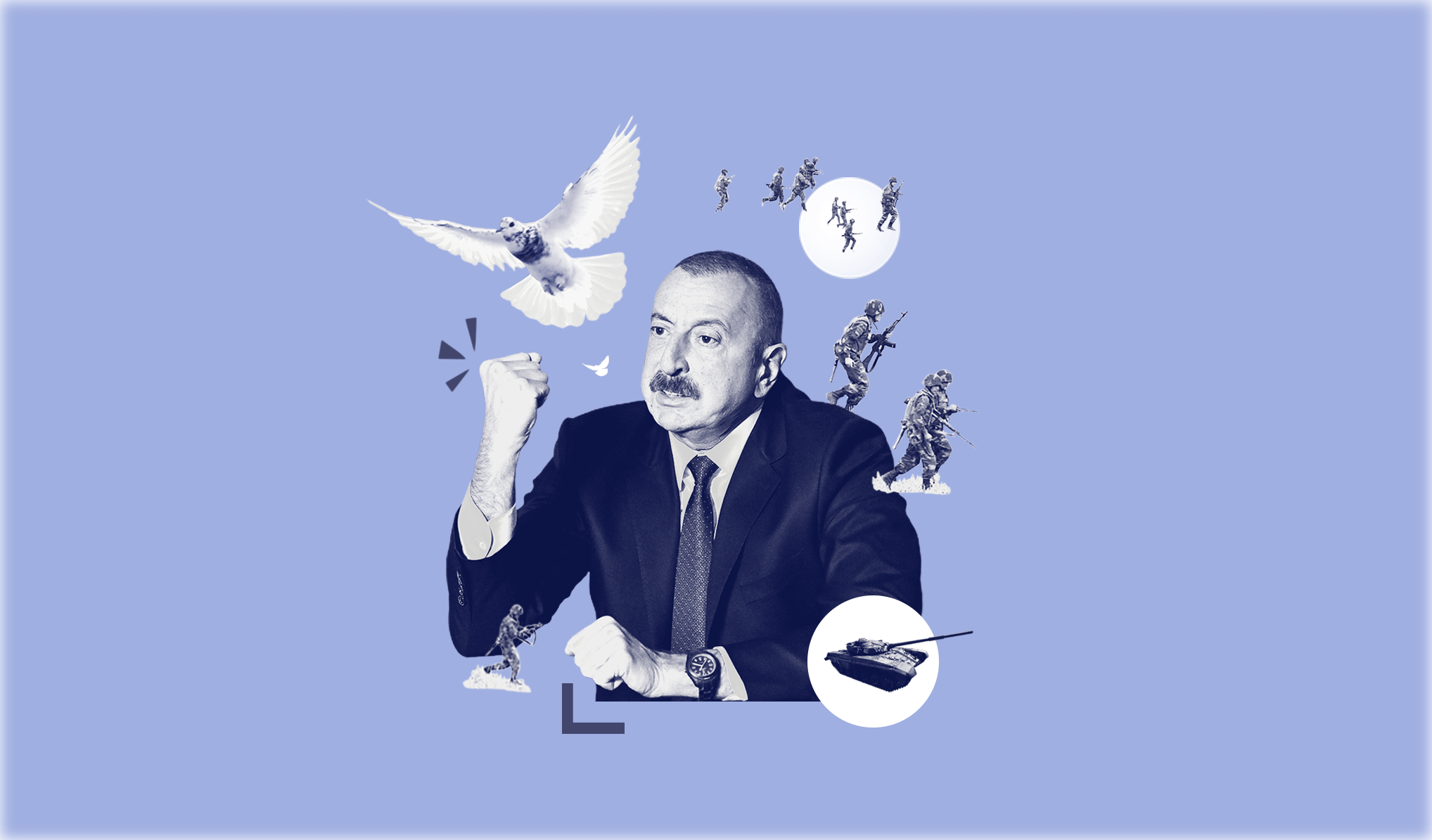

Perhaps an even greater barrier to peace than ethnic tension, is Azerbaijan’s own government. Azerbaijan is ruled by a fully authoritarian regime that shows no respect for human rights, even to its own citizens. Since 1993, Azerbaijan has been ruled by the Aliyev family like a textbook dictatorship. Meaningful political opposition in Azerbaijan is impossible. No independent media is allowed to exist, activists like Oslo Freedom Forum speaker Leyla Yunus are regularly imprisoned and tortured, and elections are a mere formality. In 2018, Aliyev was “reelected” to a fourth term with 80% of the vote, after opposition candidates were prevented from registering.

Discussions about degrees of autonomy for Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh run up against the fact that nobody in Azerbaijan, save the regime itself, has any degree of control over domestic politics, and the recent actions and rhetoric of the Azerbaijani government do not bode well for a peaceful coexistence with Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh. Several days ago, Azerbaijan’s Foreign Ministry announced that it would try two Lebanese-Armenian civilians for terrorism after kidnapping them in Nagorno-Karabakh while moving to disbar one of the last remaining human rights lawyers in the country.

Democratic reform in Azerbaijan is needed to secure future peace in the region. Azerbaijan cannot expect ethnic Armenians to be loyal citizens of a country that doesn’t allow representation or basic minority rights. Simultaneously, the democratic opposition in Azerbaijan faces a major challenge today. Victory in battle has made Aliyev popular. His wartime speeches have become part of the popular culture and images of the victory parade will surely be heavily featured in regime propaganda for years to come. Worryingly, some members of the opposition have reacted by trying to outflank Aliyev’s irredentism, arguing that the government should have gone further and seized all of Nagorno-Karabakh — maybe even all of Armenia. Meanwhile, young activists and anti-war campaigners have been labeled “sluts” by nationalist Azerbaijani bloggers.

If, as Aliyev claimed in his victory speech, Azerbaijan is committed to “long-term peace” and the “the path of justice and international law,” his government should commit to democratic reforms that would give political rights and representation to ethnic Armenians, as well as Azerbaijanis. Repeating the mass deportations and ethnic violence of the early nineties will only lead to more violence in the future. As difficult as democratic reform may seem today, it is the only viable path toward reconciliation and eventual peace in the region.

Alexander Sikorski (@AKSikorski) is a Program and Policy Fellow at the Human Rights Foundation.