By Carolina A. Miranda

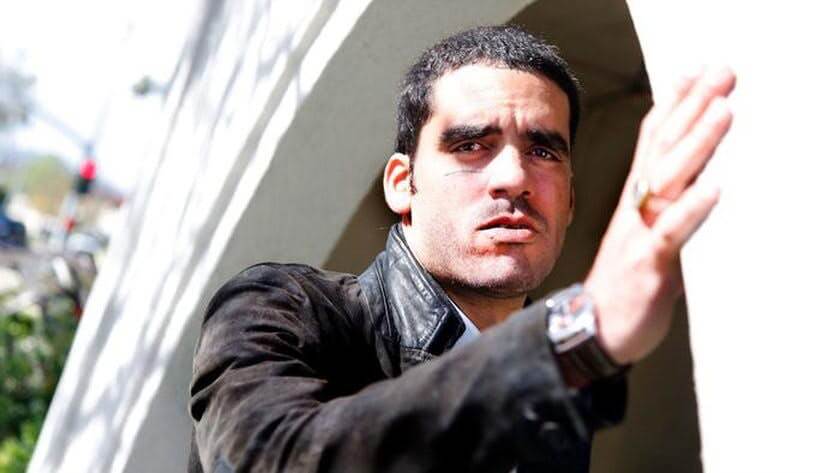

At the tail end of 2014, Danilo Maldonado Machado, the graffiti artist known as “El Sexto,” was detained by the authorities as he made his way to a public park in Havana to stage a work of protest art.

In his vehicle, he was carrying a pair of pigs that he had painted with the names of the Castro brothers — one “Raul,” the other “Fidel.” His plan was to release them and let members of the public catch them and take them home.

But the piece, titled “Rebelión en la granja” (after George Orwell’s “Animal Farm) never happened. Instead, Maldonado spent 10 months in jail. His case drew international headlines. As did a subsequent detention in which he publicly celebrated the death of Fidel Castro on a Havana street.

Maldonado now finds himself in the United States where he is promoting human rights in Cuba in collaboration with the Human Rights Foundation, which helped fund his U.S. trip. (The Visual Artists Guild and various private donors funded the L.A. portion of his travels.) He is also at work on a pop-up exhibition that lands in San Francisco in mid-May. “It will feature a variety of things, like a reconstruction of the cell I was in in Cuba,” he says. “There will be drawings and paintings.”

The artist was in Los Angeles recently for a one-night show of his prison drawings at the Stay Gallery in Downey. He also participated in a panel at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles, in conjunction with a screening of the documentary “Patria o Muerte: Cuba, Fatherland or Death,” directed by Olatz Lopez Garmendia and executive produced by Julian Schnabel, that looks at the difficult economic and political circumstances facing everyday people in Cuba. (Maldonado is featured in the film.)

In this edited conversation, he discusses why he is drawn to graffiti, what inspired him to attempt to release a pair of pigs in Havana, and the children’s book he would one day like to write for his daughter.

You have made your reputation as a street artist. How did you get your start?

I always drew as a kid — always. And I had lessons because my uncle was an art critic. As an adolescent, though, I got bored with the formal education in school and wanted to get away from that.

I started noticing the importance of visuals, of propaganda, of how those things can affect people. [The Cuban government] has appropriated everything. All of the TV shows are by the government. All of the newspapers are by the government. All of the billboards are by the government. I wanted my art to relate to that. I was interested in graffiti because it was a type of street propaganda.

What were your earliest actions?

“Rewind” — I used to paint the rewind symbol, the two little arrows, using a stencil. I put it all over the place and they started to erase it, so I could tell they were keeping an eye on the streets. But I still chose the street because I didn’t have to ask anybody’s permission.

How did the name “El Sexto” come about?

It’s a joke. Like I said, I’m interested in publicity and propaganda. In Cuba [in the 1990s], there was this gigantic publicity over this group called the “Five Heroes” [the Cuban Five] — these five spies that were arrested in the United States. I thought, if they are the Five Heroes, then the sixth hero is the people. So I became “El Sexto” — The Sixth. I started putting it all over the place as a joke, as propaganda.

What inspired “Rebelión en la granja,” the performance piece with the pigs?

I’m always looking for a way of grabbing visual space, not just by graffiti. That’s why I do things like transmit live on social media. I’m trying to invade the visual spaces of others.

Well, in Cuba they do this thing with pigs where it’s like a game. They release some pigs and you pay 20 pesos and you go into this area and whoever gets the pig, gets the pig. I was like, “I’m going to paint these pigs green and write their names “Raúl” and “Fidel” on them.

I had them in the truck on my way to the park. I told a friend to get on the phone and publicize it, so they found out about it and they picked me up. They accused me of desacato — which is having a lack of respect for maximum authority. And well, the maximum authorities are the Castros. They talked about putting me away for three years. I did 10 months.

Your work has a sharp political message, but also humor.

For me, the humor is so important. People want to laugh. And with humor, you can demystify these people. They have these uniforms that they’ve invented for themselves, this status; with humor you can pick it apart.

How do you and your work fit into the broader art scene in Cuba? What connections do you have to some of the island’s better-known artists?

The only thing that is recognized as art there are the things that are within government institutions. If you are outside of that, it’s not art, it’s not anything. The galleries are theirs, the museums are theirs, the institutions — the ones who will do the paperwork so you can travel — those all belong to the government.

I have some relationships with some of the “official” artists, but given my condition, as someone who has been a prisoner, they can’t expose themselves too much by helping me out. I don’t judge the decisions that someone makes in this regard. They have families that they have to take care of. Everyone has stuff they need to do. I also have family, but I choose to be free.

How connected are you with Cuban artist Tania Bruguera (who was also detained for attempting to stage a performance in Havana)? And how do you feel about international artists becoming involved in Cuban politics?

She’s a friend. I worked in a school that she created in Havana [Instar, the Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt]. The level of what she represents, it’s so important. It’s like Julian Schnabel [who spoke out on my case]. These are people who have international recognition and they managed to spread the news of what was happening to me in Cuba. That’s what people like Tania can do: They can draw attention to the cause. Cuba needs the solidarity of the world.

When the dictator died and they picked me up, everyone got right on social media supporting me. It was really beautiful.

As Cuba and the U.S. reestablish diplomatic relations, has there been an economic and political opening in your view?

Not really. You have all of these foreign investors, but it doesn’t make much of a difference in the life of the average Cuban. If some company comes and opens a cafe, they don’t pay the employees directly. They pay the Cuban government, and the government pays the people. And the official average wage is still $20, $25 a month. People say, “Oh, we have relations with Cuba now.” No, you have relations with the government of Cuba, not the people.

What works were you exhibiting in Downey?

I was showing some drawings I did in prison — some from the first time around, when I was arrested for painting the two pigs.

There are some drawings from this last time I was in jail, when [Castro] died. I had gone out into the street and written “Se fué” (He’s gone) as a graffiti on the building where the revolutionaries had installed themselves after the revolution triumphed. It was the Hotel Habana Libre, which before was the Havana Hilton. That graffiti cost me two months of jail time.

And there were drawings from a small book I started making for children — for Renata María, my precious girl. She will turn 4 in July.

A political book?

No. It’s not about inserting politics. It’s very imaginative.

Where I live there is the issue of propaganda and dogma, and they start it from the youngest age. They are constantly manipulating — there are these books with drawings that say things like “En manos buenas, un fusil es bueno” (In good hands, a rifle is good) and feature images of people dressed in fatigues.

I wanted to do something different. This features magical elements. It has things about flying through the clouds. It has things that are very childlike.

What did being in prison teach you about Cuba?

It’s that the majority of people who are in jail, even though they wouldn’t consider themselves political prisoners, they are political prisoners. They are prisoners because they don’t work for the state — and that’s dangerous to the state. If you sell peanuts because you don’t want to work for the state’s miserable wage, you can end up in prison.

But [the Castros], they’ve never been held responsible for the crimes they have committed. On the contrary a lot of people think [Fidel] is cool. There are a lot of people in Latin America who think he is cool. But that’s not cool. Cool is Gandhi. Cool is Martin Luther King Jr.

El Sexto will showcase his art from May 11 through May 25 in ‘Danilo Maldonado Machado: Angels and Demons,' an event hosted by Human Rights Foundation at Immersive Art Lab, 3255 Third St., San Francisco. For more information, see HRF's Facebook.

Read the original article on The Los Angeles Times.